Spec Dinosauria: Titanosauria

From Saecula Novae

To most humans, the sauropod is the archetypal dinosaur. These long-necked colossi were the dominant terrestrial herbivores throughout the Jurassic and Early Cretaceous, their fossil remains turning up across the globe. On Spec, the sauropods are alive and well, but nowhere near as widespread they once were. They are represented by a single lineage, the aptly named titanosaurs “ the largest land-animals on the planet.

Titanosaurs first appeared in Jurassic as long-necked browsers but did not become successful until the Cretaceous as the rest of their kin went into decline. Throughout the Late Cretaceous and into the Palaeocene, titanosaurs flourished across the globe, especially in the south. At the dawn of the Eocene, the titanosaurs of the northern hemisphere became extinct while their southern cousins fared a little better. The climatic chaos that struck the planet at the end of the Eocene ended the reign of the sauropods in Antarctica and Australia, while a lone South American genus (Acrotitan) lingered on until the end of the Oligocene.

For reasons that are as yet unclear, only Africa continued to sustain healthy populations of titanosaurs. Even here they had to contend with increasing aridity and the decline of the forests that had sustained them since the Mesozoic. By the Miocene , most titanosaurs had abandoned the tree-browsing diet of their forebears and had evolved to exploit new lifestyles. Today, titanosaurs are represented by about ten species, of which all but two are highly atypical compared to their Cretaceous ancestors. Although they have spread out from their ancestral homelands into southern Eurasia, the African continent remains their stronghold.

The titanosaurs are rather unusual sauropods when compared with their extinct brethren. They have simple, unforked vertebral spines and well developed dermal armour that provides protection as well as back-support by means of ligaments between the plates. They effectively lack fingers in that their forelimbs lack any sort of claw or hoof, terminating in a fleshy pad. Their caudal vertebrae have a unique ball-and-socket articulation makes the tail strong yet flexible. Typical titanosaurs have highly pneumatised skeletons, on par with some maniraptors, with a system of air-sacs that save weight and prevent overheating.

Aside from their great size, titanosaurs are striking amongst living dinosaurs in their phenomenal juvenile growth rates. A newly hatched sauropod is less than a metre long, yet after a year of ravenous feeding, it will have tripled in length, gaining on average 2 kg of mass each day. Within a decade, it will have become a giant, multi-ton adult.

NEOBRACHIIDAE (Gihugrongos)

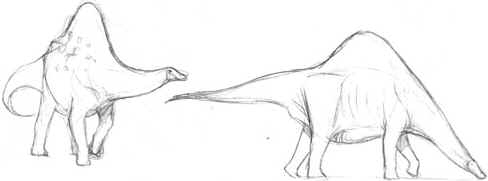

The gihugrongos are conservative, high-browsing titanosaurs that convergently resemble the distantly related brachiosaurid sauropods of the Mesozoic. They possess elongated forelimbs, a short tail and very long, stiff neck that holds the head well above the rest of the body. These adaptations allow the gihugrongos to access foliage high in the trees, well above the reach of most other herbivores. Their snouts are equipped with large, chisel-like teeth that they use crop twigs and fruit. While about twenty extinct forms are known with a fossil record extending back into the Oligocene, only two species survive today in Africa.

Watching dryforest gihugrongos (Neobrachius altissimus) pluck at the branches of manglar conifers in the African dry forests and tree savannas, one is transported back to a bygone era when similar beasts roamed across the planet. These colossi still commonly reach 14 metres in length and are thought to reach 8 tonnes in weight, although, understandably, none has ever been weighed. Adult dryforest gihugrongos have no natural predators with all but the largest of black beasts giving them a wide berth.

Although dryforest gihugrongos can produce quite some devastation, they are the only dispersers of the seeds of many manglars. Because of these sauropods, the trees are more widely distributed than one would expect otherwise.

Gihug An adult rainforest gihugrongo is somewhat bigger than it's dryforest cousin, reaching 16 metres in length and probably exceeding 10 tonnes in weight. It is close to 6 metres tall at the shoulder while its head can reaching twice as high into the air. An awe-inspiring animal for sure, but still a pipsqueak when compared with some of its extinct predecessors which were twice as long.

These little-known sauropods are restricted to the lowland forests of the Congo Basin. Found either as solitary animals, in pairs or in small herds, rainforest gihugrongous have a profound impact on the rainforest vegetation thanks to their insatiable appetites. Day and night they plough through the forest like a living combination of bulldozer and steamroller, noisily forcing their way through the undergrowth. The tendency of rainforest gihugrongos to follow regular pathways through the jungle has led to a network of deep-trodden "gihugrongo-highways" up to 4 metres wide that are devoid of trees and creates an open canopy that allows sunlight to reach the forest floor, creating microhabitats for entire biotas that live nowhere else. Rainforest gihugrongos usually feed on the move, stripping leaves from branches on either side of the highway, each individual at its own height.

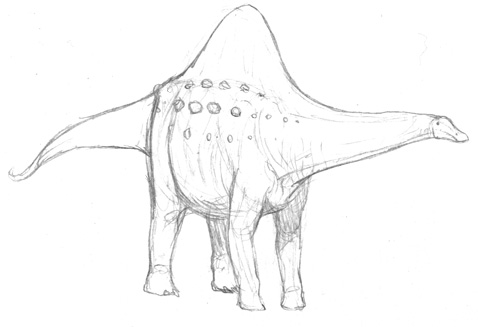

NEOTITANOSAURIDAE (Grassbags)

The grassbags, the giant grazing sauropods of the grasslands and savannah, evolved in the early Miocene from high-browsing forms that took advantage of the tree savannas that spread across much of Africa. Such a dramatic shift in lifestyle has led to many anatomical changes from their ancestors. The extremely long and slender neck of their ancestors became progressively shorter and more robust. This adaptation allowed for a larger skull with more powerful jaw muscles to tackle tough, fibrous grasses. Sharp chisel-like teeth were packed into tight, cropping batteries at the front of the square-shaped snout. To cope with increasingly arid conditions the neural spines on the dorsal vertebrae became elongated to form an immense sail, both for the anchorage of fat reserves and as a radiator of excess heat.

The grassbags spread rapidly across Africa and into Eurasia during the Miocene. However, the comings and goings of the Ice Ages has led to a high rate of species turnover in the north with several waves of extinction and reintroduction occurring during the late Pliocene and Pleistocene. Today, two grassbag species reside in Africa, with a single additional species in Eurasia.

MOKELESAURIDAE (Mokeles)

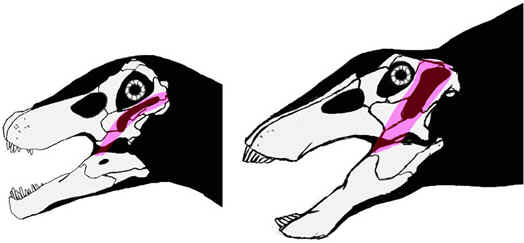

The mokeles are small to medium-sized titanosaurs that, by virtue of their ability to colonize remote islands, have become the most diverse family in the titanosaur group. The mokelesaurs are adapted towards an amphibious lifestyle, and actually resemble the popular outmoded Home-Earth reconstructions of Jurassic sauropods. Mokeles have robust, barrel-shaped torsos and comparatively short limbs. Like the skeletons of many diving birds, their air sacs no longer invade the bones, keeping them solid and heavy and allowing the animals to stay underwater with little effort. The more derived of the two extant genera (Mokelesaurus) has eyes and nostrils positioned on protuberances at the very top of its skull, allowing the animal to breathe and survey its surroundings while remaining mostly submerged. As they are smaller than other titanosaurs and often share the waterways with a variety of big, nasty predators, mokeles have the most extensive armour protection of any sauropod. This armor consists of a combination of closely packed ossicles, rounded scutes and triangular spines. Mokeles feed on a wide variety of aquatic foliage ranging from riparine weeds to marine seagrasses.

The Nile mokele, largest of modern mokele species (surpassed only by the extinct Mokelesaurus gargouille, which lived in large parts of Europe during the Pleistocene interglacials) is nevertheless a rather small sauropod. This amphibious titanosaur can reach lengths of 12 meters and weights of 6 tonnes, though individuals this large are rare.

Nile mokeles rule the rivers and wetlands of Africa. These sauropods live like hippopotami, walking along the riverbottom while placidly plucking at aquatic vegetation, sometimes using their necks to reach foliage growing on the riverbanks without leaving the water. They are often accompanied by swarms of fish that either snatch up small invertebrates in the kicked-up silt or graze on algae growing on the dinosaurs' scaly flanks. Formidable armour renders the adults effectively immune to attack from the large crocodiles that share their habitat. Brooding mothers lay their eggs in a simple, fiercely guarded pit on the riverbank. The hatchlings are 65 cm long and form creches among the reeds and sheltered pools.

6.5 million years ago the Mediterranean Sea evaporated. A series of tall mountains, their slopes blanketed in lush greenery, provided a welcome refuge for dinosaurs that ventured into the salt-encrusted basins from Europe and Africa. Then, a little over one million years later, the Atlantic burst through the straits of Gibraltar, filling the Mediterranean basin and stranding whole communities of animals on the mountains which had suddenly become remote islands. Now facing conditions radically different than those on their ancestral continental homelands, the isolated Mediterranean dinosaurs began to venture down peculiar evolutionary pathways. The small became large while the large became small. By far the most striking example of this insular size-shift are the minimokeles.

An adult male Sicilian minimokele (Minimokelesaurus insularis insularis) reaches a length of just over 4 metres and weighs 450 kg. While still a substantial animal by human standards, this half-pint would be lost in the shadow of its continental cousins. More terrestrial in habit than mainland mokelesaurs, they feed on a wide variety of leafy vegetation as well as seaweed in the shallows.

Females and young travel in tightly knit groups whilst the adult males tend to be solitary and territorial, fighting off rivals with a tail-club made of fused osteoderms. Although non-avian theropods have not become established on most of these islands, the minimokeles are still subject to roc attack and have their dorsal surface protected by closely packed armour scutes. The minimokeles that were initially discovered on Sicily are presently the best studied population of these dinosaurs. Other minimokeles were subsequently found on Sardinia, Corsica, Crete, Cyprus and many other Mediterranean islands. Those on Malta ( M. i. kawai) reach a mere 330 kg, the smallest known adult sauropods, living or extinct. Although currently lumped together as M. insularis, minimokelesaurs from different island groups show proportional differences and preliminary research suggests that at least three separate species are involved.

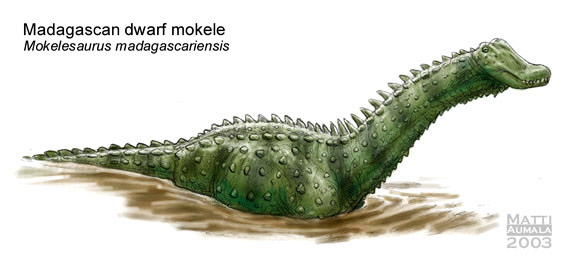

Just as hippos did on Home-Earth, so did the mokeles successfully make the ocean crossing from Africa to the island of Madagascar. As they made themselves at home in waterways that were rather more modest in size compared to the ones on the mainland, they evolved smaller body-sizes to cope with less abundant resources, eventually becoming an insular dwarf species.

The 5.5 meter long Malagasy dwarf mokele looks a lot like a half-sized version of the Nile mokele, with its bony armor and flattened, muscular tail. It has remained anatomically similar to its African cousin and is still mainly aquatic. The only notable difference with the Nile mokele is the flexibility of the neck, which allows the dwarf to feed from low-growing trees. They can be found in suitable freshwater habitats throughout the island.

- Brian Choo , Daniel Bensen, Matti Aumala and David Marjanovic