Cenoceratopsia (Spec)

From Saecula Novae

CENOCERATOPSIA

Across the warmer parts of the globe, herds of giant herbivorous ornithopods dominate the landscape. However, when trudging through the forests and swamps of tropical Asia, and to a lesser extent tropical Africa and South America, observers will often come face to face with dinosaurs of a very different kind – the parrot-beaked ceratopsians.

HISTORY

The ceratopsians first appeared in Early Cretaceous Asia and soon branched into two successful Laurasian groups (among several smaller ones). The Asian Protoceratopsidae were comparatively primitive forms that were usually hornless or, at most, in possession of a small nasal horn. While staying small, they became exceedingly abundant in places like the arid plains of Mongolia. Far more spectacular were members of the North American family Ceratopsidae which attained huge sizes (sometimes surpassing today's Indian megahorn, see below) and sported a dizzying array of facial horns, spikes and bosses. During the Campanian perhaps a dozen species of these frilled giants marched along the western shores of the interior seaway. However, as the Maastrichtian progressed, ceratopsid diversity waned.

The family made a comeback of sorts during the Palaeocene and Early Eocene, evolving into spectacular behemoths such as †Brontoceratops, the most massive ceratopsian ever known. Alas, these magnificent beasts vanished around the Eocene-Oligocene boundary.

At the same time, however, their smaller protoceratopsid cousins were having a more productive time. They grew larger and stranger, moving into niches vacated by their recently departed cousins. In terms of higher-level diversity, the Late Oligocene was the heyday of the protoceratopsids when a variety of weird lineages could be found throughout the Northern Hemisphere.

As the Neogene dawned, a number of factors conspired against this parrot-beaked menagerie. The Haughton impact at the close of the Oligocene led to localized extinctions in Asia and practically wiped them out in North America. Finally they quite certainly had difficulty coping with the spreading grasslands. The narrow beaks and slicing dentition of most species was great for tearing into tough bark and cycads, but considerably less efficient at processing grass than the square bills and grinding teeth of hadrosaurs. While the other groups dwindled, one line of protoceratopsids abandoned the characteristic scissor-teeth of their ancestors, allowing them to exploit a wider range foods (although they never produced a specialised grazer). These were the Caenoceratopia, which by the Late Miocene had regained much evolutionary lost ground. They soon became the dominant large browsers of southern Eurasia and made headway into Africa.

During the Pliocene or perhaps end-Miocene, they entered North America and marched across the Panama isthmus to become established in South America for the first time (as far as we know) in ceratopsian history. Then came the climatic seesaw that was the Quaternary. The lush woodlands which the ceratopsians favored appeared and vanished with the ebb and flow of the glaciers to the north. Today the caenoceratopians are no longer present in North America and northern Eurasia; but they continue to thrive in the warmer parts of Asia, Africa and throughout South and Central America.

FEATURES

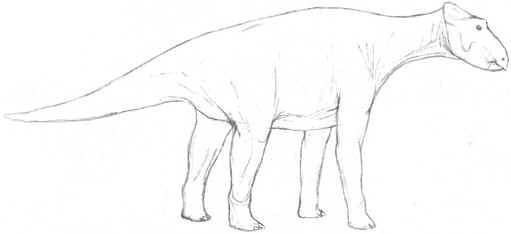

One glance at its homely face is enough identify the creature in front of you as a ceratopsian. A unique bone called the rostral sits at the tip of the snout and, when combined with the predentary at the tip of the lower jaw, creates a narrow beak. Jutting out the back of its skull is a frill of bone formed by the parietals and squamosals. This frill can be used for display as well as providing an extended surface area for huge jaw muscles, giving the animal a formidable bite. Members of the extant clade Caenoceratopia share a number of additional features which separate them from their protoceratopsid ancestors. The ischium is now fairly straight, losing the pronounced downward curve. On the face, many of the ornamental features of the long extinct Ceratopsidae have convergently re-evolved, including horns on the nose and brows. Unlike the smooth-edged frill of protoceratopsians, those of caenoceratopsians may be decorated with prominent knobs and spikes.

The most characteristic feature is, however, in the teeth. The tooth batteries of early ceratopsians were arranged to form a set of vertical blades. In effect, they chewed their food with a set of garden shears – a trait which probably allowed them to subsist on tougher vegetation than their contemporaries. (This feature is still used by the undaurs, which in general eat tougher stuff than the gihugrongos with which they coexist.) However, it is difficult to imagine this mechanism as being anywhere as effective as the grinding batteries of hadrosaurs.

When the caenoceratopians appeared in the Late Oligocene, their dentition progressively shifted towards a duckbill-like configuration where the crowns of the teeth rasp against each other to crush and grind plant food. This made chewing far more efficient than in earlier designs and was probably the key to their success. However, the teeth of caenoceratopians can easily be distinguished from those of hadrosaurs in being fewer in number, more robust in form and two to four times larger relative to body size. The teeth often bear prominent cusps and ridges which helps them to process plant matter that most ornithopods consider unpalatable.

PLATEOCEROTIA (Dawnhorns, megahorns...)

These are fairly primitive and generalized caenoceratopsians that are currently restricted to Asia (one species, the African megahorn Furciceratopoides africanus, lives in the African thorn-bush savannas), but include the giant extinct monocerotids of North America. All plateocerotians possess a well-developed nasal horn or series of nasal hornlets as well as parietal and epocciptial spikes on the frill. They have a fairly long, low-slung bodies and short, down-curved tails. Unusually, the hatchlings are born with one or two pairs of large fang-like premaxillary teeth which may be retained, reduced or lost in the adults.

Plateocerotia and Potamoceratopidae (see below) share a number of features, including enlarged teeth for the grinding of hard fodder, a small nose horn, and a number of biochemical similarities.

PLATEOCEROTIDAE

This Asian clade contains two living species that are characterized by a total lack of osteoderms and unusual crushing dentition. The nasal horn is large and unusually broad based. They are creatures of dense tropical forest and woodlands, using their powerful teeth to break open the fallen seeds and nuts of rainforest trees.

The dawnhorn is a 4 metre long caenoceratopian that dwells in the forests and woodlands of southern Asia. Males of this species have a curious, laterally flattened nose horn, which flushes bright yellow-orange during the mating season and has inspired this creature's common name. These ceratopsians root around on the forest floor, consuming fallen branches and fungi whilst browsing on low foliage in clearings and at the forest edge. Their specialty, however, is in the consumption of the tough fallen fruit of several kinds of rainforest tree.

The most remarkable feature of the dawnhorn is in the mouth. Pair of stout, triangular premaxillary teeth is present in the roof of the mouth while the cheek teeth are massive and robust. In short, the dentition of the dawnhorn has become a giant nutcracker and it is one of the few animals capable of tackling a fruit as intimidating as a zlatkonut.

The half-dozen or so species of zlatkopalm (Marjanophytaceae) are a relict group of unusual primitive angiosperms found only in tropical Asian lowlands. These remarkably ugly, foul-smelling and fast growing small trees or bushes produce immense fruiting bodies all year round. These so-called zlatkonuts are protected by an incredibly resilient spiny husk, superficially similar to a WWII naval contact mine. The dawnhorns eagerly snatch up these fruits when they fall to the ground or use their powerful beaks to violently rip them from low-growing species. Once in a dawnhorn's mouth, a powerful biting action brings its teeth to bear on the husk and the zlatkonut is soon noisily cracked open. The ceratopsian then feeds on the stuff inside, a slimy pulp, which contains the seeds of the zlatkopalm. These pass through the dinosaur's digestive tract to be deposited on the forest floor a few days later within a pile of beautiful, nutritious poo. The dawnhorn is thus a vital element in the reproduction of these plants, which is why the zlatkopalms do not grow in otherwise suitable habitats where these ceratopsians are absent.

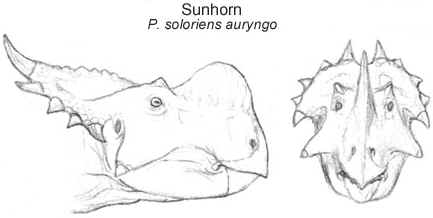

Auryngo/sunhorn, Plateoceros soloriens auryngo (southern Nepal)

The auryngo or sunhorn is a subspecies of dawnhorn that was at first mistaken for a species of its own by early specbiologists. The auryngo lives only in the Terai region (southern Nepal) while P. soloriens soloriens is more widespread, and can be found throughout mainland Southeast Asia. At least two more undescribed subspecies dwell on the islands of Sumatra and Borneo whilst an entirely new Plateoceros species has recently been discovered in southern India.

FURCICERATOPIDAE

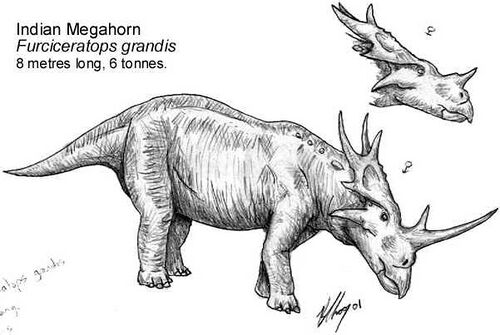

The furciceratopids form the largest living group of ceratopsians, with perhaps a dozen species, ranging from small forest dwellers to the giant megahorns. Apart from one species, the abovementioned African megahorn, they all live in Asia. They have generalised dentition, a large narrow nasal horn or series of hornlets and prominent jugal spikes. Most have spiny or stud-like osteoderms set in their scaly hide. They tend to be unfussy feeders, eating any greenery they can easily get to.

Although nowhere near as nearsighted or red-green-blind as Home-Earths rhinos (similar-looking giant mammals), most of the larger species are known to be extremely bad-tempered. Even giant priscataurs will usually give an adult megahorn a wide berth. Smaller forms, on the other hand, can be extremely shy and cryptic.

Research suggests that the extracts of the megahorns' horns possess an extremely potent aphrodisiac quality and could form the basis of a highly lucrative pharmaceutical trade.

Indian megahorns, the largest living furciceratopids , range from eastern India to the shores of the South China Sea. Females and young live in small herds whilst adult males are usually solitary. Their preferred habitat is grassland and open areas in forests, usually close to a watercourse where they wallow and bathe. Their powerful beak can demolish even the toughest of plants.

African megahorn, Furciceratopoides africanus (Africa)

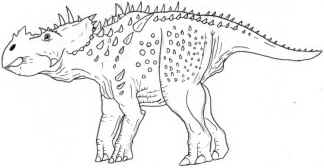

The African megahorn (Furciceratopoides africanus) can be found in all rain-green forests of Africa (except at the highest altitudes) where it munches on the undergrowth. Not quite as immense as its Indian relative, it is still an impressive sight.

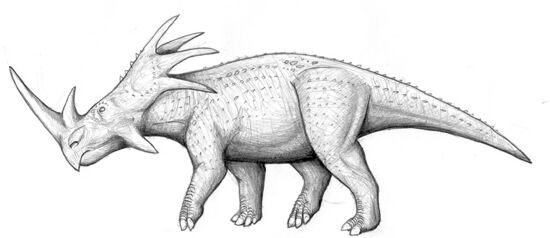

Spec is plagued by cryptic ceratopsians! While the frill-tusker/till-cheek dinoceratopian debate rages on in South America, this strange little Indian dinosaur has gone virtually unnoticed. Known only by its scientific name Terramoloch spinifer, this enigmatic ceratopsian long frustrated specbiologists by refusing to fit in with any other ceratopsian clade. Many believed (and some still maintain) that T. spinifer is a Eurasian dinoceratopian, but with the aid of mitochondrial DNA studies, we have concluded that T. spinifer is, in fact, a close relative of the Indian megahorn.

Terramoloch spinifer (south Asia)

To compare the massive Indian megahorn to the tiny Terramoloch – which measures less than two meters in total length – at first seems as ridiculous as comparing the little herbivore with the frill-tusker, but a number of physiological, as well as genetic features support this hypothesis. Firstly, the branching nasal horn is diagnostic of Furciceratopidae, the clade to which the megahorns belong. Also, the enlarged, curved jugal horns (once touted as links to the dinoceratopians) are present in many megahorns, including the Indian megahorn. Even the bizarre covering of spiny scutes, unique among ceratopsians, is present (though to a much lesser degree) in young megahorns.

The habits of T. spinifer are largely unknown, but this denizen of the high plateaus of India and Nepal seems to be a low-level browser, feeding mostly on roots and shrubs, p-Rhododendron being this species' food of preference. T. spinifer's mating and child-rearing behaviors are unknown.

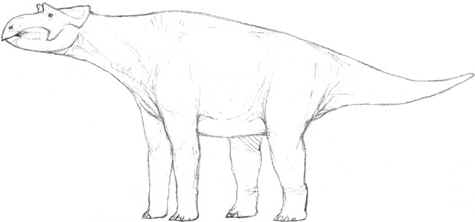

POTAMOCERATOPIDAE (Behemoths)

The behemoths are large, massively built semiaquatic dinosaurs that roam the bottom of rivers and lakes if southern Asia in large herds. They feed primarily on aquatic plants but will sometimes come onto land to browse after sundown. The legs of behemoths are rather small, and they usually move slowly on land. The neck is short, and the tail is strongly shortened, so that crocodiles can't attack easily. Behemoths have massive heads with short frills, and long barrel-like bodies. Their eyes and nostrils are positioned at the tops of the skulls and protrude from the water when these dinosaurs rest near the surface.

Each of the major tropical Asian river systems plays host to at least one species of these aptly named river behemoths. Males of some species have horny growths above the eyes in addition to the small nose horn.

The Indian river behemoth is the largest behemoth species, and can weigh up to 8 tons.

Indian river behomoth, Potamoceratops obesus (South Asia)

BRACHIOCERATOPIA (Undaurs and the horned riddle)

These giant beasts are considered to be the most highly derived of the caenoceratopians. The premaxillary teeth have been lost, as has the fifth finger. The pronounced sacral curve of most other ceratopsians is gone making the tail stick out roughly horizontally from the body. The head is comparatively small and possesses a number of weight-saving features, most notably a reduced neck-frill with large parietal fenestra. The neck vertebrae have been greatly elongated and buttressed save for the first four which, as in other ceratopsians, are short and fused to assist in supporting the skull. Except for the neotenic dwarf undaur, all adult brachioceratopians possess incipient brow horns, epoccipital studs or spikes and a single row of triangular dorsal scales along at least the length of the tail.

ENIGMATOCERATOPIDAE

The enigmatoceratopids are basal brachioceratopians which were most diverse in the late Miocene. Today they are restricted to a single diminutive species from Southeast Asia. (see the Horned Riddle)

BRACHIOCERATOPIDAE (Undaurs)

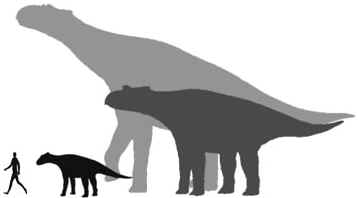

The three Asian brachioceratopid species shown to scale. The two African species are within this size range.

These enormous graviportal high-browsers of tropical Asia and Africa are the giants of the Caenoceratopia. Along with the pseudosauropods of South America and the extinct indricotheres of our timeline, they have done a marvellous job in ripping-off the gihugrongos, even though they don't reach the sizes of the biggest ones. Their skulls are lightweight (although retaining a pair of stubby brow horns) allowing the greatly elongated neck to raise the head high into the trees. All four limbs are pillar-like; the forelimbs are elongated and are now held straight under the body, losing the characteristic "bow-legged" posture of other ceratopsians. The tooth-batteries of brachioceratopids have also been reduced in size as a weight-saving feature, and the undaurs have reverted to a system once used by their distant ancestors but long since abandoned by the rest of the Caenoceratopia: they swallow stones, storing them in the gizzard to grind up plant-matter after a brief chewing-phase in the mouth. Nevertheless, the cutting power of their jaws allows them to eat food too hard for gihugrongos, and their digestive system allows them to live off leaves that severely hinder the digestion of gihugrongos; on the other hand, gihugrongos have no problem with stuffing themselves with conifer needles, while undaurs avoid them, probably because of their tannines and their low nutritious value.

Young and adolescent undaurs stay close to one another whilst the adults are generally solitary. Breeding may occur throughout they year. A male in "dinomusth" will aggressively clear an area of rival bulls before trumpeting loudly to attract receptive females. Egg-laden females gather together in small herds before depositing their brood in pits on the forest edge and going their separate ways. The newly hatched young frantically scamper into the darkness of the undergrowth where they spend up to five years before leaving to form an adolescent herd. Unless in the mood for mating, adult undaurs are the most peaceful of all ceratopsians, lacking the jittery shyness of the smaller forms and the psychotic aggression of the large low-browsers. When one flick of your leg can send a priscataur flying, you can afford to be docile.

Brachioceratopidae evolved during the Oligocene, after the enigmatic extinction of sauropods in the northern hemisphere, and soon produced such giants as †Titanoceratops.

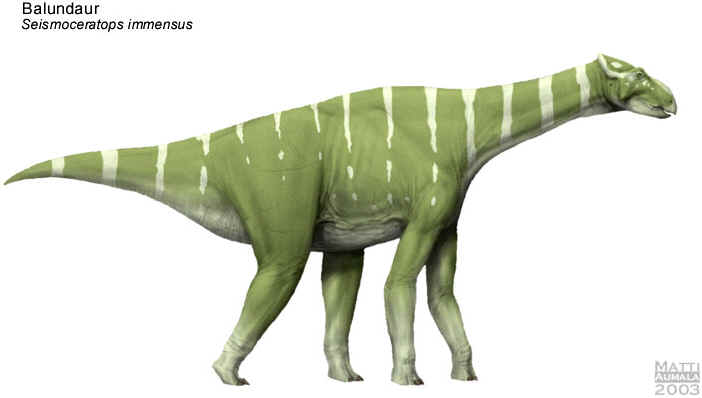

Indian balundaur, Seismoceratops immensus immensus (Asia south of the Himalayas)

Standing before an adult 15 metre long balundaur (Seismoceratops immensus) gives takes one to new levels of humbleness. At up to 14 tonnes, this is quite certainly the largest living ornithischian, surpassing even the giant neotropical pachamacs. Balundaurs may be spotted throughout the Indian subcontinent to as far southeast as Borneo and Sumatra, but are not found north of the Himalayas. They can be found just about anywhere where they are trees, roaming far and wide in search of fresh greenery leaving a trail of dung and destruction in their wake – providing opportunities for a host of other organisms.

A small herd of eastern balundaurs, Seismoceratops immensus orientalis, with greater perfects, Commensasaurus adamsi, fiery mulong, Mulongia longipes, and lots of painted jaubs, Trichromatornis immensophilus (southeast Asian mainland)

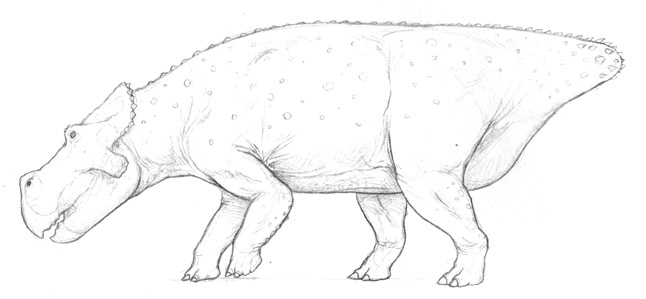

The common undaur (Brachioceratops dynastes) is nowhere near as large as the towering balundaur (10 metres long, 7 tonnes) but is still an impressive animal, nonetheless. Unlike its larger cousin, the greater undaur prefers to stay close to forested environments, venturing out onto the wooded plains only in particularly bad years. As a result of its wider distribution coupled with a more restricted habitat requirement, up to six different subspecies of this creature have cropped up in India, Sri Lanka, China and Southeast Asia.

Common undaur, Brachioceratops dynastes (south and southeast Asia)

The placement of the sishundaur (Brachioceratops microgigas), a remarkable, little known animal, as the closest relative of the greater undaur is a point of some contention. Found only in the dense upland forests of Java, the sishundaur looks to be nothing more than an overgrown hatchling greater undaur (ca. 4 metres long, ca. 500 kg). Like a hatchling, the body is compact and dumpy whilst the brow horns, studs on the frill and bony scales on the back (which all other brachioceratopians acquire when over 2 m in length) have not developed. It scales also bear an almost identical cryptic spotted pattern to the juvenile greaters.

Sishundaur, Brachioceratops microgigas (Java)

However, one of these "big-babies" was witnessed laying a clutch of 25 eggs which were unfortunately plundered by an unknown raider before they hatched (whatever it was also chopped/bit the two field researchers who were watching over the nest to handy pieces). All in all, this animal would appear to be an extreme case of neoteny, and it has been suggested that it is no more than a mutant form of the greater undaur, a subspecies of which occurs in the Javan lowlands.

DINOCERATOPSIDAE

(See Link: Dinoceratopsidae (Spec))

,=P. s. soloriens (Dawnhorn)

,=Plateocerotidae=Plateoceros sloriens=|

| `=P. s. auryngo (Sunhorn)

,=Plateocerotia=|

| | ,=Furciceratops grandis (Indian megahorn)

| | ,=|

| | | `=Terramoloch spinifer (Terramoloch)

| `=Furciceratopsidae=|

| `=Furciceratopoides africanus (African megahorn)

,=|

| | ,=Potamoceratopsidae=Potamoceratops obesus (Indian river behemoth)

| `=|

| | ,=Enigmoceratopsidae=Enigmoceratops faustuosus (Enigmoceratops)

| `=Brachioceratopsia=|

| | ,=B. dynastes (Common undaur)

| | ,=Brachioceratops=|

| | | `=B. microgigas (Sisundaur)

=Cenoceratopsia=|

| `=Brachioceratopsidae=|

| `=Seimoceratops immensus (Balundaur)

`=DINOCERATOPSIA